Over 1,000 environmentally sustainable dwellings have been built in the Yaodong cave area of the Loess Plateau in China using traditional energy saving methods and vernacular housing design. The low-cost houses are built through self-help construction and the use of innovative solar energy systems and natural ventilation methods help to reduce energy consumption to a minimum.

Project Description

Aims and Objectives

- To build the public awareness of sustainability in the Loess Plateau, including energy saving, farmland saving and natural environment conservation.

- To enhance villagers’ and local institutions’ ability to design, plan and manage their shelter to meet much higher living standards.

- To enhance access to improved affordable housing for the residents in the rural area of the Loess Plateau.

- To create a new model of yaodong dwellings which not only inherits the energy-efficient features of traditional ones but also is fit for modern life and attractive to rural dwellers whose wealth is increasing.

- To reduce energy consumption.

- To avoid the loss of traditional and appropriate vernacular housing design.

- To develop the skills of people in both rural and suburban areas in the construction of the yaodong dwellings.

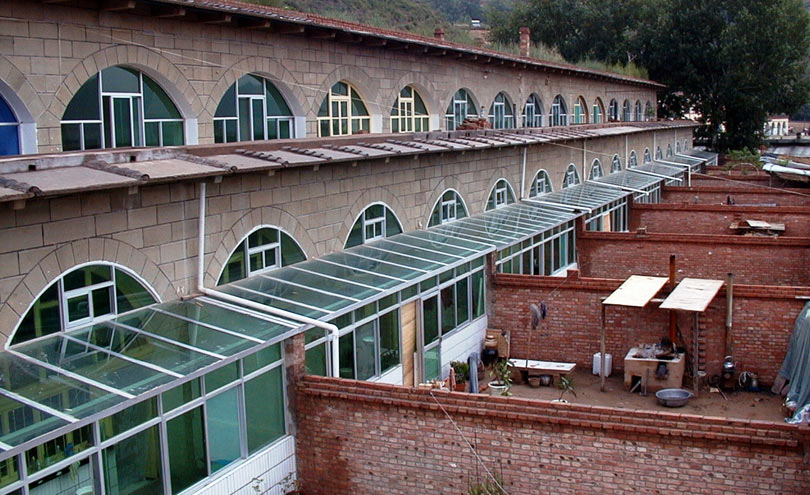

Located in north central China, the Loess plateau of undulating hills covers nearly 500,000 km2. Forty million people live in this region, 75 per cent of whom are farmers in rural areas. Living conditions are amongst the lowest in China, although some incomes are now increasing and there is a widening income range. Ninety per cent of the rural population live in various types of yaodong, or cave dwellings. The earliest types of these were dug into the hillsides and they have since evolved into masonry dwellings that are more disengaged from the mountainside (only 10 per cent are still in the dug-out form, 70 per cent have their rear wall abutting the mountainside and the remainder are entirely freestanding). One family dwelling usually consists of two or three arched openings and the units are interconnected inside. The spaces between the arched shapes are filled with earth to make a thick flat roof. The free-standing yaodong dwellings differ from ordinary free-standing houses in that traditional designs and simple materials are used as well as a traditional cluster configuration, to maintain a strong sense of community.

With the rapid growth of China’s economy, most rural people want to live in new, modern housing and tend to be dissatisfied with the traditional yaodong dwelling. As they become wealthier, many younger people prefer to build concrete structures where there is a large increase in energy usage and pollution, valuable farm land is used and there are impacts on the natural ecosystem. There is a risk of loss of the indigenous building traditions, a trend that is already well established in the rapid urbanisation of China’s eastern cities.

Starting with a pilot project of 85 houses in Zaoyuan village (1996-2001), the project has now seen the development of over 1,000 dwellings by families using self-help construction methods in both rural and suburban areas. In addition, a private real-estate developer has built a further 1,200 dwellings plus two large hotels.

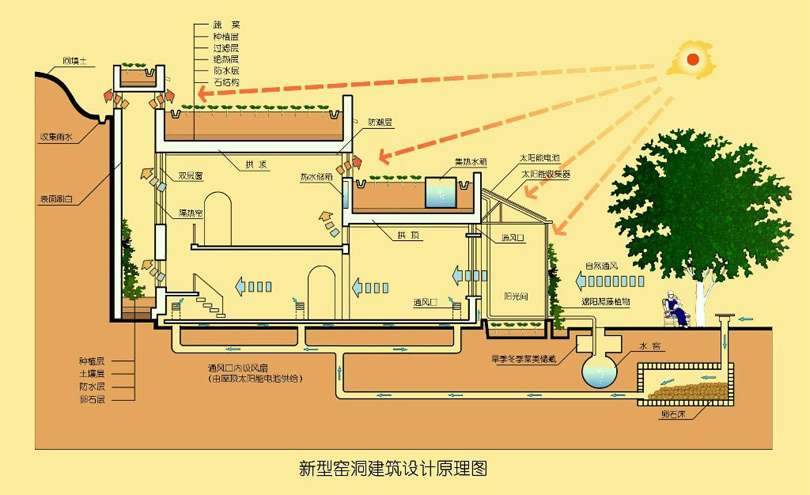

The new housing design is based on the traditional design but increases the one-storey yaodong to two-stories and includes a sunspace at the front and earth-sheltered roofs, which serve to increase the indoor daylight levels, as well as improving natural ventilation and humidity. The new design has been developed in cooperation with the residents and continues to enable traditional lifestyle practices. The houses have roof planting and thermal mass protection. Although the houses are low-cost they are sufficiently modern to be attractive to the local people.

Innovative solar energy systems and natural ventilation methods have been successfully introduced whilst still retaining the traditional arched yaodong front which has cultural significance. Local people are involved throughout the design and construction process and the Yan’an local government has been supportive.

Each dwelling unit is approximately 80-100 m2,and costs of construction are ¥220 per m2 (US$27 per m2). Total cost per dwelling is thus US$2,160 – US$2,700. This cost does not cover land, courtyard or decoration. The average annual income of a villager is ¥2000 (US$250). As there is no state subsidy provided, this housing is not affordable for the very poorest rural households but it is possible for the relatively better-off villagers to afford them. Technical support provided by the Green Building Research Centre (GBRC) is free because the costs are met by national government funding.

Residents, members of the village administration, local artisans and officials are involved in the design of the dwellings. They work with the university researchers who live in the village while this work is carried out. The residents continue to maintain the homes as owners of the properties. All new dwellings are initiated and completed by the residents.

The sense of cultural continuity is very important. Surveys have shown that the residents feel that the new yaodong is not something imposed on them from the outside, but rather it has grown out of their lives and is a continuity of their building tradition. The resident’s subjective opinion of the new dwelling and involvement in the design and construction process is considered to be an important aspect of the sustainability of the housing, of equal importance as the energy- and pollution-saving aspects. Friends and neighbours of the residents help them to build the houses, using their traditional building skills.

The pilot project was completed in 2001 and the house-type developed continues to be constructed, with over 1,000 houses completed by villagers and even more by private real estate companies.

Why is it innovative?

- Establishing a new model house for the rural population that is connected to local and traditional roots, but that meets changing social and economic circumstances and expectations (unlike most Chinese modern architecture that is using western models).

- Use of two-storey construction rather than single-storey in order to increase the amount of functional space available.

- Zero consumption of energy for heating, ventilation and air conditioning due to the use of solar energy and natural ventilation systems.

- Use of earth sheltering building methods on top of the traditional arch construction in order to increase the thermal stability.

- Recognition of the value of the residents’ input into the design and construction process.

What is the environmental impact?

The design involves using the local topography to provide the housing structure, thereby reducing the need for roofing and wall construction materials. The building materials used are sourced locally and recycled building materials have been used wherever possible.

The use of solar spaces helps to reduce the need for internal heating. The earth sheltering nature of the design means that even at external temperatures of -20°C, the internal temperature can be maintained at 10°C, with only the use of a traditional kang (stone bed linked to an internal stove).

Old style Yaodong dwellings consume 15 kg of coal per m2 for heating; concrete houses require 25 kg, whilst new yaodong dwellings require 0-5 kg. With a CO2 emission ratio for local coal at 2.4:1 the CO2 emission saving per property is 2,400 kg (2.4 tonnes) for a 100 m2 dwelling. The project has resulted in CO2 savings and minimisation of pollution from the construction process through the use of existing terrain and minimal construction materials.

The houses are cut into hill terraces on land that is infertile or hard to farm, thus maintaining the amount of land available for agriculture.

Is it financially sustainable?

Since there is no government support and the housing costs are funded by the families living in the houses, the project does not rely on an external source of funding. The costs of GBRC technical support are met by a national government subsidy which will be continuing.

Retaining young people in the area with more modern housing helps boost the local economy and prevents the downward spiral associated with rural depopulation.

The cave dwelling homes of the area have been promoted as a tourist attraction (due to historical connections with the early days of Mao-Tse-Tung). The world’s largest cave dwelling complex (in the north of Yan’an city) has been converted into an eight-storey hotel with 300 rooms. Some retain the traditional heated stone bed; others have ordinary beds to meet the demands of tourists.

The costs of the new yaodong dwellings are approximately half of that of the new flats being built using western methods and materials in the nearby towns and this helps to encourage local young people to stay in the rural area.

Utility bills are lower since the new design provides greater warmth in the dwelling through the use of the sunspace at the front of the dwelling.

What is the social impact?

People work together with their friends and neighbours to build their own homes. The design of the housing is more conducive to people meeting their neighbours than living in one of the new flats in the local towns. Construction skills and knowledge of energy saving have both increased as a result of the project and the retention of local young people helps to maintain the community infrastructure.

A healthier living environment in the houses has bee created due to the improved ventilation and a reduction in the damp levels through enhanced heating.

Participation in the design process is very innovative in this context, and has been particularly valuable because the GBRC clearly attach high importance to the comments of the residents.

Barriers

Both the traditional understandings and new aspirations needed to be challenge. Young people want a modern city-type dwelling as the desire to match western residential standards is pervasive; older people prefer the old-style dwellings and don’t want to change and the local government wants any modernisation to look like London, Shanghai or Beijing.

Lessons Learned

Residents need to be advised on how to take greatest advantage of the new dwellings and demonstration houses are important in winning over local residents to new design ideas. An entirely local design process is impossible because residents equate modern, non-local building materials with progress and an increase in status.

Ecological principles need to be applied differently in urban and rural areas since there is greater emphasis in the rural areas on retaining some of the traditional design values. High tech solutions and expensive methods are not appropriate in these rural areas. Promoting low-tech solutions will not win local residents over unless there is a significant increase in living conditions. In this case this was achieved with an increase in the air quality in the dwelling.

Evaluation

Monitoring has been carried out on the 85 dwellings built as part of the pilot study. This looked at the thermal performance and occupants’ satisfaction. Residents were closely involved in the monitoring process. It was found that indoor temperatures are higher on average by five degrees in the new buildings (i.e. increasing from 10 to 15 degrees at midday) and indoor daylight levels and ventilation are much improved in the new buildings.

Transfer

Starting with a pilot project of 85 houses in Zaoyuan village (1996-2001), the project has now seen the development of over 1,000 dwellings by local families using self-help construction methods in both rural and suburban areas.

Variations on the design have also been used by a local real-estate company and a further 1,200 dwellings have been developed using the new designs, as well as two large hotels. A new yaodong dwelling community has been established in the eastern suburb of Yan’an city and a second one is under construction. Several private entrepreneurs have plans to develop in the Loess Plateau (Gansu and Shaanxi provinces).

Academics and architects from other parts of China have visited the project and developed similar projects to improve vernacular architecture and make it more energy efficient. For example, Professor Jiang Shuguang from Shi He Zi University in Xinjiang Province is developing a new kind of dwelling for rural people. What is common in these efforts is the idea that new forms can be developed that can carry the traditional values of a local community; that this is a part of what it means to be ‘sustainable’.

Professor Liu Zheng from Polytechnic University of Inter-Mongolia is developing a new kind of improved vernacular (tented) dwelling for the Mongolian rural population.

Partnership

NGO/Private